Cuernavaca, 1979. Just 85 kilometers south of Mexico City, this sun-drenched city had long been a favored escape for the wealthy — a place where the climate was temperate, the villas were grand, and discretion was understood. Former president Luis Echeverría kept an estate here, and actress María Félix frequented its famous garden restaurants and glamorous private parties. For both Mexico City’s elite and international celebrities, Cuernavaca offered a weekend getaway from the capital’s chaos. For the Shah of Iran, it was a getaway of a literal nature.

A king without a kingdom

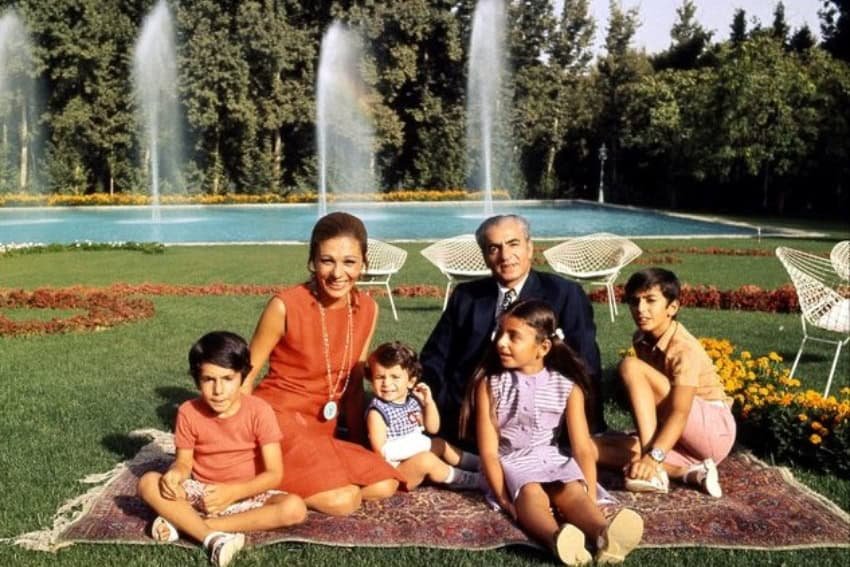

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, colloquially known simply as the Shah, was a controversial figure in Iranian history. His reign began in 1941 when his father was forced to abdicate the crown. For nearly 40 years, the Shah westernized Iranian society, launching programs that strengthened land reform, industrial growth, expanded education and women’s suffrage. However, his lavish lifestyle and repressive tactics created societal friction, and by 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini took control of the Persian powerhouse and the monarchy fell. The Shah was exiled.

He left Tehran in January, spending brief stints in Egypt, Morocco and the Bahamas before declining an invitation to settle in Panama. It was Mexico that had been on his mind for years, and it was in Mexico that he wanted to live. In his memoir, “Answer to History” — written largely during his exile and published posthumously in 1980 — he noted that he had “enjoyed its scenery and people” during a 1975 state visit to Acapulco and various archaeological sites, including Chichén Itzá. A warm relationship with José López Portillo, whom he had known as Mexico’s Finance Minister before López Portillo became president, strengthened the appeal. For all of these reasons, Mexico ranked first on what the Shah described as his own list of preferred places of exile — and thanks to a deal brokered partly with the U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Mexico accepted him.

90 days on Avenida Palmira

With their Bahamian visas set to expire in two days, Mexican authorities extended an official invitation to the Shah, his wife — Farah Pahlavi, known formally as both the Empress and the Queen — and their 18-year-old son, Reza. Aides flew ahead to scout a location, settling on a vacant villa on a prestigious, tree-lined stretch of road called Avenida Palmira, then known for its grand French-inspired homes. The family landed at Mexico City International Airport on June 10, 1979, where a small motorcade was waiting to take them south. The Villa del Shah, as it came to be known, sat near a riverbank surrounded by lush gardens and rolling countryside. It was beautiful — though the Shah noted in “Answer to History” that the area was, less romantically, “thoroughly infested with mosquitoes.”

According to a report by Infobae supported by The Washington Post, the family rented the villa for $1,000 per day. Security was elaborate: three concentric rings of protection surrounded the property at all times, totaling 72 people — 12 Iranian agents in the innermost circle, 20 Americans in the middle ring, and 40 Mexican agents in the outer perimeter. Inside, the household ran as the Shah had been accustomed to in Iran. Meals were multi-course affairs of meat and fish, wine and champagne, all served on sparkling silver or gold-plated dishware. The Shah received notable visitors during this period, including Henry Kissinger and former President Richard Nixon, both of whom paid personal visits to the villa. Otherwise, the family kept largely to themselves, socializing very little with neighbors or the wider community.

Table 14 at Las Mañanitas

The Shah and his family were rarely seen in public, with two exceptions. The first was the Racquet Club, where the Shah and his son Reza played tennis. The second was Las Mañanitas, a celebrated garden restaurant set among lush grounds filled with exotic birds, which remains one of Cuernavaca’s most storied dining destinations. According to Infobae, the family always sat at table 14. Security staff would arrive at varying hours ahead of them, order a single drink, and occupy the surrounding tables until the family was ready to leave.

The Shah typically requested something light — often a dish the staff called pollito con leche, a very tender preparation served with steamed vegetables. His son Reza, by contrast, had developed a taste for Mexican food and usually ordered sopa de tortilla. Word spread quickly, and visitors began making the trip from Mexico City and Puebla simply for the chance to glimpse the royal family from a distance.

Nonetheless, the Shah spent most of his time in the villa working on “Answer to History,” his account of his reign and the revolution that ended it. He was also making plans for the future — commissioning the construction of a fortified private mansion nearby that he and his family could call their own. According to a 1987 Los Angeles Times article, the three-story walled structure was to include seven bedrooms, eight and a half bathrooms, seven fireplaces, a spa, an outdoor pool and a grand terrace. It was completed in 1981. The Shah never saw the finished product. He died in 1980.

A secret illness and an unwanted one-way ticket

Throughout his time in Cuernavaca, the Shah was carrying a secret he had kept even from his Mexican medical staff, who were treating what they believed to be malaria when called for his severe case of jaundice. He had been quietly battling lymphoma for six years. David Rockefeller, then-Chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank and a longtime supporter of the Shah, knew of the true diagnosis and sent a private physician to the villa. It is worth noting that Rockefeller’s concern may not have been purely out of the goodness of his heart — Chase Manhattan Bank had extended a $500 million loan to Iran shortly before the Shah’s exile, giving Rockefeller considerable financial interest in the former monarch’s survival.

By October, the Shah’s condition had worsened to the point that his medical team determined he required treatment that could not be provided in Mexico. On the 22nd of that month, the Shah and the Empress made their way back to Mexico City International Airport to board a Gulfstream jet bound for the U.S. for admission to a New York hospital. News of his arrival, along with photographs and reports showing his failing health, quickly signalled to the public that the ex-world leader was seriously ill.

The Shah’s Mexican visa renewal request denied

His treatments concluded at the end of November, and the Shah fully expected to return to Cuernavaca. His Mexican visa was set to expire on Dec. 9, but he had reason for confidence — President López Portillo had told him on two separate occasions to consider Mexico his home and that he was welcome there. However, while making final travel arrangements, Mexico unexpectedly rescinded the invitation.

According to a New York Times report on Nov. 30, it was the Iran Hostage Crisis that caused a sudden change of heart. Mexico’s Foreign Minister issued a formal statement: “In the face of this new situation, the Mexican Government has pondered all the essential factors, aware of its duty to protect above all the vital interests of the nation. It has reached the conclusion that it would be contrary to these interests to renew the tourist visa granted to the ex‑Shah.”

Legend, legacy and what remains

How Cuernavaca’s residents felt about their elusive royal neighbor is difficult to say. The family kept so thoroughly to themselves that the Shah remained more rumor than reality for most locals — which perhaps explains why the most enduring story from his time there cannot be verified. According to an urban legend that still circulates in the city, a helicopter flew over the villa on Avenida Palmira one night and riddled the building with machine gun fire in an assassination attempt, forcing the family to flee to a safe house — possibly the Hotel y Spa Hacienda de Cortés, which still maintains a Suite del Shah today. No evidence has ever surfaced to confirm the story, and it is most likely just that: legend. But in a stay defined by secrecy, it is perhaps unsurprising that myth rushed in to fill the gaps.

The former Iranian royal family never returned to Mexico. The Shah died in Cairo, Egypt on July 27, 1980, less than a year after leaving Cuernavaca. His 90 days in this quiet Mexican city had been, in many ways, one of the last peaceful interludes of his life: a period of garden lunches, tennis matches and long hours spent writing his account of a world that had already disappeared. Empress Farah Pahlavi still survives her husband, and divides her time today between Paris and the Washington, D.C. area. Their son Reza lives with his family in a suburb of Washington as well.

The Shah’s life remembered in Cuernavaca

For those who want to see where that chapter unfolded, traces of history remain. Table 14 at Las Mañanitas still sits among the birds and gardens of one of Cuernavaca’s most beloved restaurants. The Hotel y Spa Hacienda de Cortés offers overnight stays in its Suite del Shah. And on Avenida Palmira, a luxury development now stands on the land where the Villa del Shah once did — the original house long gone, but the address not forgotten.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog or follow her on Instagram.