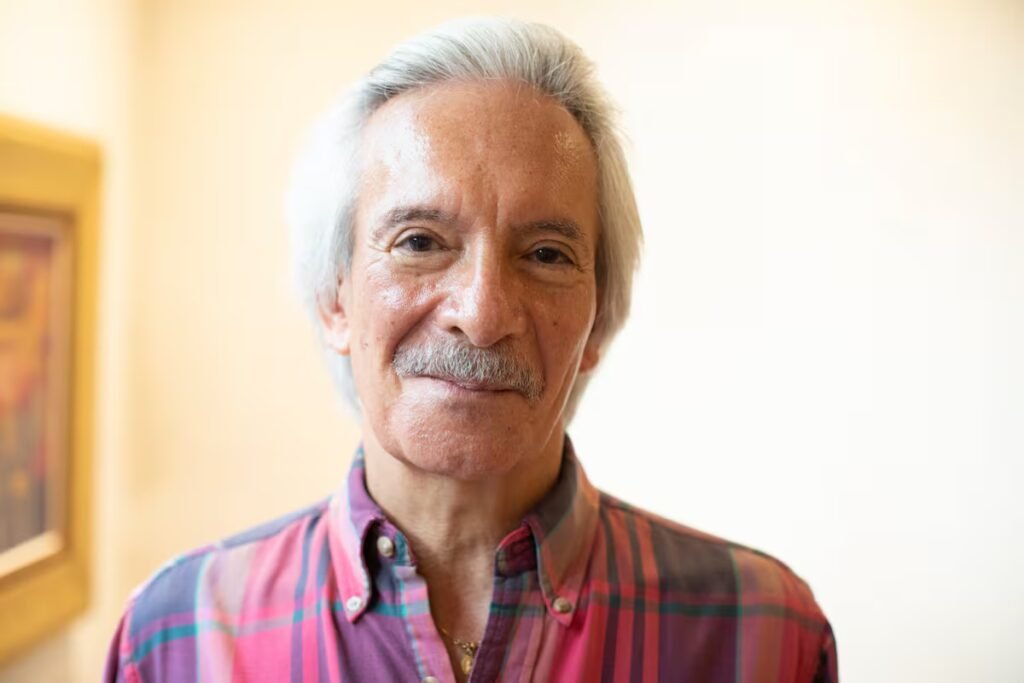

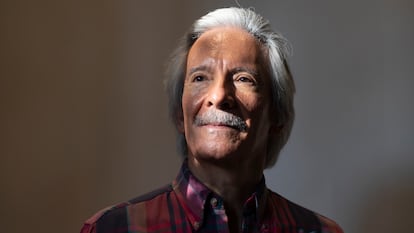

Guatemalan journalist José Rubén Zamora (Guatemala City, 69 years old), who was granted house arrest last week, faces the possibility of being returned to prison after the Prosecutor’s Office appealed the judge’s decision on Tuesday. Zamora receives this newspaper in the quiet living room of his home, in an affluent neighborhood of the capital, a spacious house surrounded by vegetation that has once again become his refuge after leaving the 12-square-meter cell — “bartolina,” he calls it — that he occupied for more than a year. He walks with relief, but also cautiously: he knows that the Public Prosecutor’s Office, led by the controversial Consuelo Porras, has him under surveillance and that his freedom is fragile.

Zamora spent over 800 days in the Mariscal Zavala military prison, in a process that international organizations and some of the foreign press have described as political retaliation. “I have essentially been kidnapped,” he says. He was arrested in July 2022 on charges of blackmail, influence peddling, and money laundering. In June 2023, he was sentenced to six years for money laundering, fined 300,000 quetzales (about $37,500), and acquitted of the other charges.

The ruling was appealed by both the prosecution and the defense. Four months later, an Appeals Court overturned it and ordered a retrial. The founder of independent media outlet elPeriódico was granted house arrest in 2024 while the case was being resolved, but only for five months. Later, another court accepted an appeal based on procedural flaws and again ordered a new trial, which has yet to resume.

He says resentment doesn’t consume him. He wants to regain weight, enjoy his children and grandchildren, and make sense of the years he has left. He doesn’t know if he’ll ever run a media outlet again, or if the system that imprisoned him will ever lose power. He has only one certainty: that one day he will be a free man. In Guatemala, that conviction sounds almost like an act of faith. If the prosecution’s appeal is successful, he could return to prison. For now, freedom is a spacious house, open windows, lush vegetation, and the awareness that the lock could close again.

Question. The Public Prosecutor’s Office has appealed the house arrest order granted to you. How do you interpret this belligerence in your case?

Answer. They’re asking for me to be returned to Mariscal (prison). Frankly, it’s mentally difficult to go back. However, if I have to go back, then I’ll go. I need to carefully consider how many hours I have available, because there are several things I want to do. This is interesting because it’s the result of political persecution. I have essentially been kidnapped. Since the special courts of [former de facto president] Efraín Ríos Montt, with judges who wore masks, there has never been such effectiveness as they showed in my case, and later with the people of the Indigenous resistance from the 48 Cantons and other people who have been criminalized.

Q. Why this belligerence?

A. I think it became a visceral hatred. They believe they are on a crusade against communism. They started a multimillion-dollar campaign to persuade people that the issue wasn’t impunity and corruption versus justice, but rather the far left versus the far right. They polarized society, and in the end, it became personal.

Q. Personal on whose part?

A. From Consuelo Porras and the Foundation Against Terrorism, made up of paleofascist extremists. It’s part of a network linked to the army and the extreme right. They’ve been brainwashing the population. Since 2000, when there were no social media networks, they used their television monopoly, always at the service of those in power. I’ve defined it as a paleofascist narco-kleptodictatorship. They started million-dollar campaigns saying I was a cocaine addict, a pedophile, bankrupt, and that I didn’t pay my debts. They showed pictures of my house, even included rats. Then they stormed onto social media with a dominant presence. Just as there were death squads during the armed conflict, this foundation has been a squad for the civilian assassination of people.

For decades, Zamora was one of the most prominent figures in investigative journalism in Guatemala. He published investigations into corruption, illicit financing, and power networks involving businesspeople, military officers, and politicians. His critics called him obsessive; his supporters, an editor willing to pay the price. That price was prison.

He maintains that the persecution didn’t begin in 2022, but rather in the 1990s, when he investigated military structures that survived the civil war and reorganized themselves in the democratic era, in what is known as “the pact of the corrupt”: an informal alliance between politicians, businesspeople, and judicial operators who, he claims, learned to use the Public Prosecutor’s Office as a weapon. He directly points the finger at Porras, former president Alejandro Giammattei, and the Foundation Against Terrorism, a far-right group that has promoted accusations against judges, prosecutors, and journalists. “It became a visceral hatred,” he repeats.

Q. Why do they have so much influence in Guatemala?

A. It’s local fascism. There are people in all three branches of government, contractors, former generals, former war officers. The military high command has connections with organized crime and drug trafficking. They need polarization. That’s part of what’s called the pact of the corrupt here. We denounced it for 30 years. My imprisonment allowed us to anticipate that the pattern of persecution would be replicated with other social groups and exposed our theoretical democracy to the world.

Q. Is this persecution because of your journalistic work?

A. Absolutely. It’s a battle that began in 1990. Even before that, we investigated the murder of anthropologist Myrna Mack. It was the first case where we tracked down both the perpetrators and the masterminds. That represented a direct affront to the army and the powerful special interest groups.

Days in jail

In prison, Zamora learned to measure time in 24-hour increments. He spoke to his family for 15 minutes a day and lost over 20 kilos. The most painful humiliation, he recounts, was when his wife was thrown out at the gate during a visit. “That broke me,” he admits. Those were days of isolation and solitude in which he focused on literature: he reread Latin American and European classics and reflected on his work as a journalist. He also suffered, as documented in an independent medical and psychological report that revealed the harsh conditions to which the journalist has been subjected and the impact on his health and spirits: “He suffers a devastating grief for all the life he has lost,” concluded the Basque physician and psychologist Carlos Martín Beristain, who conducted an independent assessment of Zamora’s physical and mental health.

Q. What were your days like in prison?

A. Long sentences. They destroy the family, the property, the presumption of innocence. I knew guards imprisoned for five years who were later declared innocent, but they were destroyed. Prison is the worst situation a person can experience. If someone is going to get more than five years, the death penalty is better, because the other is a slow agony.

Q. Did prison destroy your life?

A. No, thankfully not. My children remained hopeful and faithful. My wife was key. When I finally had a phone with this government, I could talk for 15 minutes a day. I learned to plan 24 hours in advance. Before, I thought about scenarios 40 years ahead; in prison, I thought about surviving the day. The first five months were incredibly tortured, but afterward, I felt free, my spirit was free. I reread the entire works of Octavio Paz. Milan Kundera died, and I reread all his work. Javier Marías, a columnist for EL PAÍS, died, and I reread not only his novels but also his columns. I read Tolstoy and Dickens more carefully. I even read 1,500-page books in three days. I was able to establish a routine, and I walked between 10 and 12 kilometers a day in 12-meter intervals. But being in prison is always dreadful.

Q. Had you imagined this scenario, being imprisoned?

A. It was always on the map. Since 1990 I’ve been persecuted. There was tax persecution under former President Alfonso Portillo and the Ríos Montt family. Eight tax officials spent three and a half years at elPeriódico. We had 89 complaints, then 198 under former President Otto Pérez Molina. In the newspaper’s 26 years, we paid around five million dollars for lawyers.

Q. What was the hardest moment in prison?

A. There were many. On May 10, I asked for permission for my wife to visit me. They verbally authorized it the night before. She came by Uber from the El Carmen neighborhood, where we live, to Mariscal, about 40 minutes away. When she arrived, they told me they were going to expel her. A guard told me, “I sympathize, but if she doesn’t leave, we’re going to drag her out and beat you up.” I had to let them expel her. They took her out of the gate, and she had to wait four hours without a phone in a shopping mall. That deeply humiliated me.

Q. Do you think the state is trying to destroy you?

A. It has been a 30-year struggle, but every story has extraordinary moments. There were triumphant advances, progress, but also setbacks. In 1995, we campaigned for the purging of state powers and forced the resignation of Congress and the entire Supreme Court. They all had to resign.

Q. Do you feel that prison has changed you?

A. It made me more aware of my age. I have maybe 10 years ahead of me, and I want to use them wisely. I went from 170 pounds [77 kilos] to 128 pounds [58 kilos]. Now I’m at 145 pounds [66 kilos]. I want to gain weight and enjoy my children and grandchildren.

The prosecution’s persecution

While Zamora was imprisoned, Guatemala experienced one of its most intense political crises since the return of democracy. Bernardo Arévalo’s victory in 2023 triggered a legal offensive to annul the result: the Attorney General’s Office attempted to suspend the winning party, raided the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, and launched investigations against officials and activists. Indigenous protests, led by ancestral authorities such as the 48 Cantons of Totonicapán, blocked highways for weeks to defend the transition.

From his prison cell, Zamora witnessed the confirmation of a theory he reiterates today: his case was not an exception, but a rehearsal. In his view, the same judicial system that prosecuted him attempted to block Arévalo’s inauguration and continues to pursue cases against exiled justice officials and journalists. He is cautious about the new government. He describes Arévalo as “a decent man,” but questions his ability to navigate the current power dynamics. “It’s tragic that in Guatemala, the arrival of a decent guy is considered progress,” he states.

Q. You mentioned prosecutor Consuelo Porras earlier. How would you define the role she has played in your case?

A. The Public Prosecutor’s Office became extremely powerful, and the lesson learned was how to use it for evil, to persecute people they disliked or who harmed their interests. In my case, it involved 142 investigations published in elPeriódico every Monday. We investigated, for example, the case of the Russian vaccines purchased through intermediaries. Congress authorized the purchase, but it was supposed to be directly from a supplier of the factory, but they bought them from an intermediary called Human Vaccine.

Q. Porras’s term ends in May. What does her departure from the Prosecutor’s Office represent?

A. The persecution will cease, and innocent people, like those from the 48 Cantons, could be freed. People in exile, who have been questioned and stigmatized in a senseless way. I hope they can be compensated, because the harm done to them is enormous.

Q. What is your opinion of President Arévalo’s government?

A. The president is a decent man. He doesn’t have great executive skills or a strong team. He has power, but he’s very respectful of institutions. It’s dramatic that in Guatemala, it’s a step forward for a decent guy to become president. In that sense, it’s been unexpected, but excellent. I think he never thought he’d win the presidency.

Q. Does he have real power or are his hands tied?

A. He has power; we’re a country that has been characterized by having “presidentitis.” The president is in charge, but he’s a very respectful man. I think Guatemalans expected more, but I believe he’ll be able to deliver a clean government in the next election because I’m sure the stealing has stopped; the scandals we used to see are gone.

Q. Is there the possibility of the president promoting profound reforms in the state?

A. I think that with these people leaving, there could be a balance in favor of the executive branch. The president was able to force the Attorney General’s resignation, but I think he’s sending us all a meta-message that we have to respect these senseless rules.

Q. Do you think your case can be resolved during this administration?

A. I would hope so. Even exiles must find a way back. Prison is agony. I know I’ll eventually be out. I won’t let resentment consume me. I want the years I have left to be the happiest.

Q. Do you plan to return to journalism?

A. It’s premature. Journalism needs resources, and today I can’t figure out how the press works now. I still read on paper. But I honor Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, Alejandro Córdova, Isidoro Zarco, Jorge Carpio. Many journalists died in Guatemala and Central America.

Q. Was it worth it for you?

A. It’s been worth it, without a doubt. There were advances and setbacks, but people didn’t give up. My life has been fascinating. I don’t regret anything.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition