Pedro de Alvarado was everything Spain wanted in a conquistador. He came from a minor noble family that had a distinguished history but few prospects. He was one of five sons and a twin to the only daughter. His home province of Extremadura, Spain, had a tradition for producing soldiers, and by the time Pedro reached adulthood, the long struggle against the Muslims was over. Thus, there was limited work for a young man with little interest in books or writing but comfortable on a horse and useful with a sword.

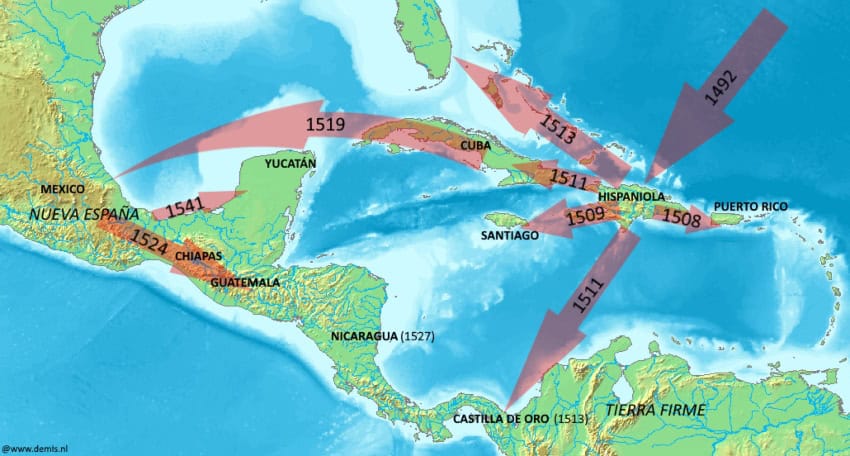

The conquest of Cuba

With few prospects in Spain, he set out across the Atlantic in the hope of improving his fortunes. This was 1510, early in Spain’s American venture, when the prospects were greater. Soon after arriving in the Americas, he took part in the conquest of Cuba. Details of the role he played are unrecorded, but Alvarado became the owner of a hacienda. As far as we are aware, the next seven years passed with him managing his lands and establishing a position for himself in island society.

Then, in 1518, he enlisted with Juan de Grijalva to join the expedition that would explore the Yucatán. Alvarado was now 33 and in his prime, moving toward financial independence and with a reputation for generosity, at least toward his Spanish colleagues.

It helped that Alvarado looked the part. Judging by the written descriptions, he was a handsome, well-built man who was something of a dandy, dressing in imported silks and velvets. Historian Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who would have known him well, wrote of his “very cheerful countenance and a winning smile.”

An early return from Yucatán

While Alvarado was a capable leader with a dash of bravado, he was not always easy to work with. For his younger officers, he was generally pleasant enough, but a fierce temper lay behind the soft commands, and he could be reckless. As de Grijalva’s fleet made its way along Mexico’s Atlantic coast, Alvarado, having pulled ahead of the rest of the convoy, took his ship into the Papaloapan River. His commander was not happy with de Alvarado taking such a risk, and shortly afterward, he used the excuse of a ship needing repairs to send Alvarado back to Cuba.

It was a poor decision, for Alvarado used his early arrival in Cuba to claim much of the glory of the expedition for himself.

An expedition to Tenochtitlán

Grijalva brought back a few gold trinkets and stories of a rich inland kingdom. This was enough to attract Spanish interest, and Hernán Cortés was authorized to prepare the next expedition. Alvarado was one of the first to sign up for the campaign. He would have been useful in many ways; Díaz also notes his skill at training young soldiers.

Having reached Cempoala, just north of modern Veracruz, Cortés left part of his force on the coast while he marched the main party inland towards the Aztec heartlands. This route took them through the lands of the Tlaxcalans, who were allies of the Aztecs.

Initially, the Tlaxcalans were aggressive but also impressed with Spanish steel, and they started to see the possibility of allying themselves with the foreigners and escaping their Mexica overlords. Alvarado particularly impressed them: Noting his powerful physique and flaming red hair, they named him Tonatiuh, as he appeared to resemble their vision of the sun god.

A diplomatic marriage and the road to Tenochtitlán

As part of the alliance, he was married to one of Chief Xicotencatl’s daughters, a woman who took the Spanish name Doña María Luisa.

As Cortés made his way inland, he sent Alvarado ahead with a small party to make contact with the Mexica ruler Moctezuma II at Tenochtitlán. At this stage, this was as much a diplomatic mission as it was a conquering army.

The story of the destruction of the Mexica Empire is well documented, and we can jump forward six months to April 1520. As negotiations continued in the capital, Cortés faced a new challenge: Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba — believing Cortés had disobeyed his orders — sent Pánfilo de Narváez to the mainland to arrest the wayward captain. Cortés departed for the coast to confront the danger, leaving Alvarado in charge of the small Spanish detachment that remained in Tenochtitlán.

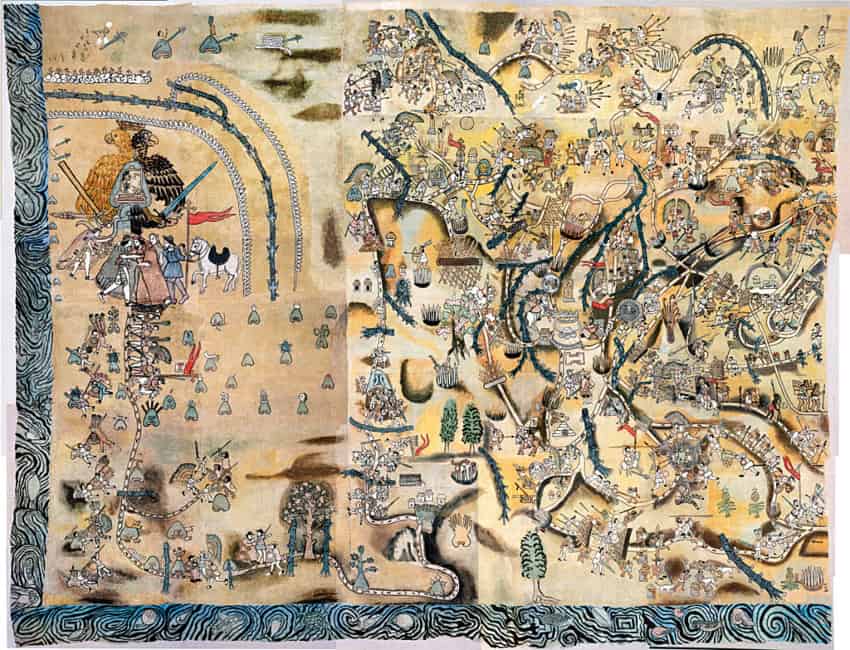

The Tenochtitlán massacre

As the day of a big festival approached, the Tlaxcalteca allies of the Spanish became increasingly nervous, fearing the Mexica would use the festival to attack them. It did not help that the best translators had gone with Cortés, leaving Alvarado with a man called Francisco, who had only rudimentary Spanish. Alvarado could have had very little intelligence of the Mexica’s real intentions.

On the night of the festival, hundreds of dancers performed in the Great Temple, making a wall of noise with their shouts and drums. Alvarado, perhaps anticipating that this was the prelude to an attack, perhaps panicking, led a brutal attack on the dancers. Hundreds of people, including the cream of the Mexica nobility, were massacred.

The city was packed for the festival, and as word of the attack spread, a mob descended on the Spaniards. Alvarado, his head bleeding after having been struck by a stone, led the survivors back to the relative safety of their base in the Palace of Axayacarl. The night had been a disaster not only for the Spanish but also for their vassal, Moctezuma, who lost the last support of his own people.

The retreat from Tenochtitlán, ‘Victorious Night’ for the Mexica

Cortés, having got the better of Narváez, returned with an army strengthened by new recruits. The situation in the capital was untenable, and the Spanish retreated to nearby Tlaxcala. Alvarado, commanding the rear guard, fought with distinction during that dangerous march out of the city. According to a disputed legend, at one point, he escaped capture by using his spear to pole-vault across a gap in the damaged causeway.

For a few weeks, the future of Spain’s influence on the mainland hung in the balance, but Cortés regrouped and once again marched on the Mexica capital. Alvarado was given command of one of the four Spanish divisions, and whatever role he had played in creating the disaster, he now made amends: On the day the city was stormed, his troops were the first to reach the city center.

A promotion and then an inquest

As the Spaniards extended their influence across the country, Cortés summoned his old friend Alvarado for a new task. There were stories that the villages of Chiapas, on the edge of Spanish influence, were being harassed by an Indigenous warrior race from the south, and Cortés wanted to explore that region.

Alvarado argued for a larger force, one that could not only identify the problem but deal with it. And so in 1524, he marched into what is now Guatemala with 300 Spanish foot soldiers, 120 horsemen and several hundred native allies.

He used the same tactics that had proved successful against the Mexica, combining alliances with brutality. Initially, this meant joining the Kaqchikel against their traditional rivals, the K’iche.

The first campaign was brought to a halt by April rains, and Alvarado, leaving his brother Jorge in charge of a far-from-pacified country, returned to Mexico City and then Spain.

To Spain and back

The Spanish trip proved a success. Having defended his actions in Guatemala, Alvarado was confirmed as governor of the new province and awarded the military title of adelantado. Ignoring his marriage to the Tlaxcalteca princess, he took Francisca de la Cueva as his wife. This was an excellent political marriage, for she had close connections to the Spanish king thanks to her influential uncle, the Duke of Albuquerque.

Alvarado’s return to New Spain proved more troublesome. His new wife died very soon after arriving, and there had been a shift in the political balance. Power in New Spain was a struggle between the old landowners and the officials newly sent from Spain, the influence of either side rising or falling on the whims of the king.

Alvarado arrived to find Cortés was out of favor, and he himself faced a formal review, a residencia for his past actions. He might even have spent a spell in prison, but Cortés, that great survivor, returned to influence, and Alvarado was free to seek new projects.

Seeking a route to the Spice Islands

South America seemed to offer unlimited promise, and in 1532, Alvarado landed off the coast of modern Ecuador. He marched inland, a disastrous trek that took a heavy toll on his force.

He returned to the coast, only to be confronted by Sebastián de Belalcázar, who had already started the colonization of Peru and wanted no Spanish rivals in the region. Too weak to offer resistance, Alvarado sold his ships and supplies to Belalcázar — both men claiming to have been robbed in the deal — and returned to New Spain.

The year 1536 saw Alvarado intervene in Honduras, where the small Spanish settlements were at odds with each other. He might well have been facing a second residencia, for in 1537, he once again sailed to Spain, most likely to bring his case before the Spanish king.

The visit went well, and Alvarado’s position as governor of Guatemala was reconfirmed for another seven years and extended to cover the governorship of Honduras. It probably helped that he had married Beatriz de la Cueva, sister of his first wife, thereby retaining the protection of the Duke of Albuquerque.

By 1541, de Alvarado was constructing a fleet to seek a route to China and the Spice Islands. Although Magellan had struggled across the Pacific in 1520, half a century after Columbus, the Spanish had still not been able to chart the tides and winds that would allow a safe journey from New Spain to the Spice Islands and back again.

An unexpected death in battle

Alvarado was sailing north along the coast and had reached Jalisco when news came of an Indigenous rebellion in the area, after a decade of brutal Spanish rule and enslavement via the encomienda system. Coming inland to Guadalajara, he was riding up a steep hill to confront the rebels when his horse slipped in heavy rain and fell on him.

The exact date of the accident is uncertain, so we do not know how long he suffered. However, Alvarado died on July 4, 1541, at the age of 55 or 56.

His will — or rather a letter outlining his wishes — was entrusted to Francisco Marroquín, the first bishop of Guatemala, who had been connected with Alvarado since meeting him in the Spanish Court in 1528 and traveling back with him to New Spain in 1529. The original document still survives.

According to the provisions of Alvarado’s will, his numerous mestizo children were to be provided for, his slaves on farms and mines were to be released and the church was to be given a new chapel. A ship builder he owed money to was to be paid.

These were honorable gestures, but Alvarado is remembered in Mexico and Latin America for his greed and cruelty to Indigenous people.

Bob Pateman lived in Mexico for six years. He is a librarian and teacher with a Master’s Degree in History.